JOURNEY TO ISLAM

Ahmed Paul Keeler

1

EDUCATED FOR EMPIRE

CHILDHOOD 1942 – 1950

I WAS BORN in Windsor in 1942, right in the middle of the Second World War. Windsor was a deeply conservative town, at the very heart of the British Empire, and the castle was the favourite palace of His Majesty the King. To grow up with a real castle of such imposing character was awesome for a child, and we children needed no encouragement to accompany our mother when she went shopping in the town, for each day the military band marched up the high street for the changing of the guard. At the entrance to the castle was a statue of Queen Victoria, who had been dead 40 years when I was born, but was still very much alive in Windsor.

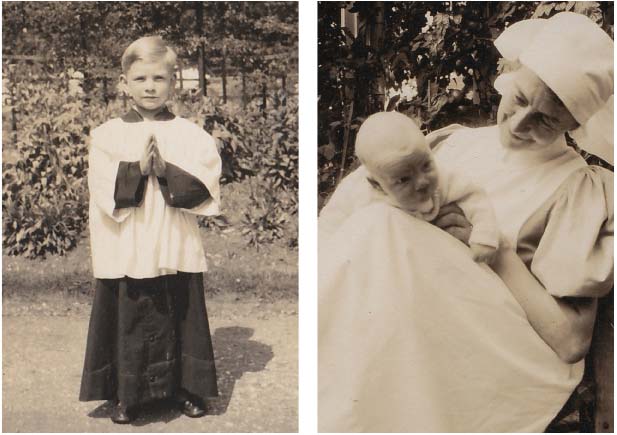

We lived in a beautiful house, surrounded by a glorious garden which was the creation of my mother, and was large enough for us children to get lost in. Through the gates to the right of the house, leading to what had been the stables, was the factory. My father was an inventor who founded a business manufacturing optical instruments, which developed into a world leader in its field. So, at the bottom of our garden we had carpentry, machine, paint and assembly shops, producing precision instruments designed by my father and his team, and exported all over the world. However, the factory and the family haven were two quite separate realms. Whereas we could roam freely in our garden and even wander into the adjoining countryside, our visits to the factory were strictly supervised as it was a hazardous place for children. The family midwife, whom we called Griffy, was a formative influence in my life. She was a true Christian and taught me to love my bible and Jesus. She took care of us when we were babies, and remained closely attached to the family until she died in her late nineties. By the age of five, I was a server in our local Parish Church and was immersed in its rituals and life. It seemed at the time I was destined to become a priest.

The family midwife, whom we called Griffy, was a formative influence in my life. She was a true Christian and taught me to love my bible and Jesus. She took care of us when we were babies, and remained closely attached to the family until she died in her late nineties. By the age of five, I was a server in our local Parish Church and was immersed in its rituals and life. It seemed at the time I was destined to become a priest.

There were five of us children; my sister was the eldest and I was the third of four brothers. We were a happy family. Our home life was full of games and activities and we seemed to spend most of our time playing outside. For our holidays we went camping in the West Country, where we set up our tents and parked our caravan in fields beside the sea, or next to a river in which we could swim. But for us boys this halcyon childhood was rudely terminated when, reaching the age of eight, one by one, we were packed off to boarding school.

PREP SCHOOL 1950 – 1956

PREP SCHOOL WAS a terrible shock, and I spent 6 years incarcerated in an institution where we lived in constant fear of the headmaster and his wife. The discipline was draconian and the food was awful. However, we formed friendships and camaraderie grew amongst us and somehow we

survived and made the best of it, and at times even enjoyed ourselves.

Games were compulsory and we played them all; football, rugby, cricket, athletics, tennis, squash, fives, shooting and boxing. For some of us it was great for others, a nightmare. To see weaker boys being beaten up in the annual compulsory boxing competition was not a pleasant sight, but we were assured it built character. We were taught to be fiercely competitive, but also we learnt teamwork and fair play. Music was another activity that brought great pleasure to some. We learnt to sing the hymns and anthems tunefully, and could take up an instrument if we wanted to.

Central to our lives was the Christian Year, with the festivals of Christmas and Easter devoutly observed. And we knew and loved the stories of the old testament prophets. But Julius Caesar and Latin were supreme in the classroom. Gentle Jesus and the warrior Caesar were the most powerful figures in our education. They were both celebrated but the contradiction in their messages was never addressed, they inhabited quite separate spheres. We knew by heart the stories of the heroes of England; Alfred the Great and the burning of the cakes, Sir Francis Drake finishing the game of boles and then defeating the Spanish Armada, General Wolf surprising the enemy by taking an army up an impossible mountainside, and winning Canada for the British Empire, the death of Admiral Lord Nelson, the saviour of the Nation against the depredations of the French. We knew little about India beyond the terrible murder of British prisoners in the Black Hole of Calcutta and the burning of widows on the funeral pyres. India was ‘the white mans’ burden’. We knew little about slavery before the great British reformer William Wilberforce and the enlightened British Parliament abolished it.

But our heroes were not confined to the past. We had just defeated the most evil force in history. And through the cinema, we were reliving the war, and the incredible stories of bravery and sacrifice that our soldiers, sailors and airmen endured. We had stood alone and triumphed; the Americans as usual arrived late, and we knew nothing of the Eastern Front and the millions that died in Russia. For this education had a purpose: to prepare us to become dedicated servants of Empire and leaders of mankind. It was based upon the Spartan philosophy, that if you took a child from its family when it was eight, you could turn it into a loyal servant of the state, and we were the last generation to be educated for Empire. After 10 years of boarding school, away from home the greater part of the year, the child, now having become a man, could be sent to any part of the Empire where the sun never set, and be expected to do his duty. Lord Macaulay had stated a hundred years before, that the English were the greatest and most civilized people that ever the world saw, and we believed this with our whole being. After all, the British Empire had surpassed Rome, our version of Christianity was the best and we had produced the greatest scientists and were the creators of the Industrial Revolution. Our mission in life was to civilise, Christianise and modernise.

I was ten when His Majesty King George the Sixth died. His image was cast upon our minds through the stamps, coins and pictures that were entwined with our lives. He was greatly respected and loved. The headmaster’s announcement of his death took place while we were having lunch, and is still crystal clear in my memory; I can see the plate of spam fritters, boiled potatoes and cabbage before me. The Nation joined with the three Queens, his mother, his wife and his daughter, in mourning his untimely death at the age of 56, exhausted by the burden of office which he carried with great courage throughout the war. A year later the young and beautiful Princess Elizabeth was crowned and became Queen Elizabeth II, and a new era began. Millions of families, including our own, bought television sets to watch the coronation, and within a short time ‘the box’ was in the corner of most living rooms, and we were being fed a diet of films and shows from America, where the TV was already well established. I was part of that last generation whose childhood was lived in the pre-television age.

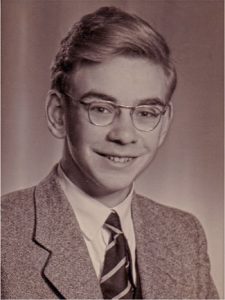

PUBLIC SCHOOL 1956 – 1960

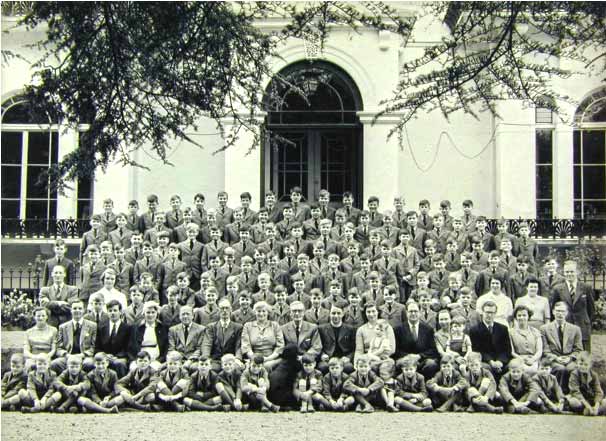

I WAS FOURTEEN when I joined my two elder brothers at Lancing College. I had had to spend an extra year at my prep school in order to pass the entrance examination. But it was well worth the wait. It enabled me to enter a world far removed from the fearful prep-school regime that had broken into my childhood. Lancing College is in a glorious setting high up in the South Downs, surrounded by countryside and overlooking the sea. In my day it was a haven of peace, yet to be spoiled by the thundering road that now links Brighton and Worthing, and the hideous additions to the school since the sixties. The College was founded in the nineteenth century, and was part of the revival of

I WAS FOURTEEN when I joined my two elder brothers at Lancing College. I had had to spend an extra year at my prep school in order to pass the entrance examination. But it was well worth the wait. It enabled me to enter a world far removed from the fearful prep-school regime that had broken into my childhood. Lancing College is in a glorious setting high up in the South Downs, surrounded by countryside and overlooking the sea. In my day it was a haven of peace, yet to be spoiled by the thundering road that now links Brighton and Worthing, and the hideous additions to the school since the sixties. The College was founded in the nineteenth century, and was part of the revival of

Christianity and the rebirth of Gothic Architecture. Lancing College with its chapel was one of the finest examples of this Renaissance. I spent four happy years in this beautiful, humane, Christian environment, where the study

and practice of art, music and drama were seriously cultivated, and were considered to be an important part of school life.

The Chapel was the highest in England and stood like a colossus above the school, dominating its surroundings. It was at the centre of our daily lives. The school came together for morning prayers after breakfast, and gathered once more for evensong at the end of the day. On Sundays and during the festive seasons, the Chapel came into its full glory, with the beauty of the architecture providing the setting for a musical feast, served up by one of the finest school choirs in England. When I was at Lancing, the Chapel was still being built, and the west end was sealed off with sheets of corrugated iron. A temporary covered walk way linked the Chapel to the School.

Our house master was a remarkable, cultured, deeply eccentric and greatly-loved character. With humour and wisdom he presided over a community where children matured into young men and the Christian virtues of kindness and compassion were cultivated through his example. In our last year, he would take a group of us on a grand tour of Italy. The year I went we visited Florence, Sienna, Assisi and Venice. With this remarkable journey my time at Lancing came to an end.

My next port of call should have been two years National Service in the army, where, coming from a public school, one would automatically be selected for officer training and then be given a platoon. However, National Service was abolished in 1960 and I missed having to do it by a month. The normal trajectory after National Service was to take up your place at university, where the education of a gentleman was completed, and then join a club where male members of the establishment continued their Public School existence. But these were not normal times. England was in the throes of a cultural revolution which, during the sixties, brought about momentous and lasting change. Our generation had been educated to take up our place in a world that no longer existed; the British Empire was over.

However, on arriving at Lancing I had found a new enthusiasm which began to replace the priesthood as my goal in life. Auditions were taking place for the school play which was to be Hamlet by William Shakespeare. I auditioned and landed a part. The standard of acting and production values for a school dramatic society where exemplary. The master in charge was a brilliant producer and well known for his adaptations of the classics for radio. Like in Shakespeare’s day, in our all-male environment, the younger boys played the girls’ parts, and I was chosen for the role of Ophelia. I immersed myself in the play, attending every rehearsal and drinking in the discussions surrounding the plot. By the time we were finished, I knew Hamlet by heart. This profound and troubling play was the beginning of my real education. The formal education in the classroom had left me cold, and continued to do so throughout my time at Lancing. I had found my niche and my passion. Nobody from my Prep school came to Lancing, so I had to make new friends which I did in my House and through the school plays which took place annually. I played Sir Patrick Cullen in the Doctor’s Dilemma by Bernard Shaw, Dogberry in Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing, and Moses in The Firstborn by Christopher Fry. At home I formed my own dramatic society, so my love of theatre carried over to the

holidays. The company was made up of friends from Lancing, my old prep school and the church.

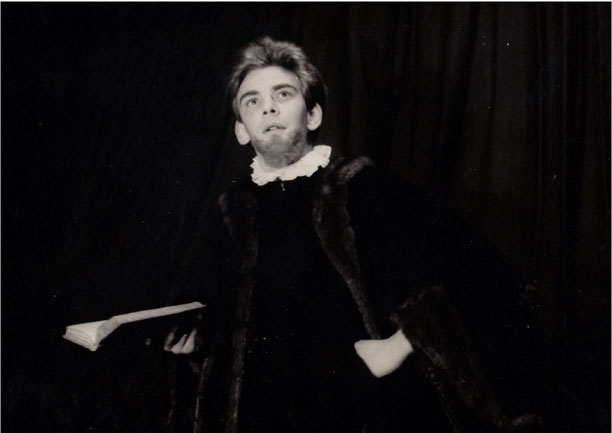

THE HEIGHT OF my dramatic career at Lancing was reached when I played Dr Faustus in Christopher Marlowe’s prescient play which envisions the birth of Modern Man. By my last year at Lancing the Theatre had become my life, to the exclusion of practically everything else. My heroes were the great classical actors of the day, at the summit of which stood Sir Laurence Olivier, whose films of Shakespeare’s Henry V, Hamlet and Richard III I saw many times.

So it was decided that, as my academic qualifications were negligible, and fell far short of getting me into any university, I should be allowed to indulge my passion, and audition for drama school. But little did I know what lay in store for me. At the age of eighteen, I stepped out into the world and landed, unwittingly, right in the middle of the cauldron of rebellion that was engulfing the arts, where I would swim, flounder and nearly drown during the first nine years of my adulthood.

2

INTO THE MAELSTROM

THE CENTRAL SCHOOL OF SPEECH & DRAMA 1960–1963

THE TWO LEADING drama schools in London in 1960 were the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and the Central School of Speech and Drama. I auditioned for the Central School and was accepted, I did not go on and try for RADA. If I had gone to RADA, my life could have been dramatically different. RADA was a drama school in the traditional mould where the classics still held sway. However, the Central School had just undergone a radical change. It had linked up with the Royal Court Theatre where the young anti-establishment playwrights were being incubated. Their production of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger had been ground breaking. At Central School, a new regime had been established and I was part of its initial intake. To begin with I had a room in a boarding house in Golders Green and travelled each day to the school in Swiss Cottage. For the first time in my life I suffered intense and aching loneliness, separated as I was from my Lancing community and friends. However, steeled in prep school to make the best of it, I threw myself into the work. We were fed a diet of unremitting angst. Our classics were the works of Samuel Becket and Bertolt Brecht, and our staple became the new British playwrights such as Harold Pinter, Arnold Wesker and, of course, John Osborne. Through their plays, they were destroying the world that had nurtured me and the values that had informed my life. The establishment, the family, the church, the army, the world of business were all targets for their brilliant, cruel, insightful dramatic constructions. In compelling language they laid bare the wasteland of broken relationships, exploitation, disconnection, and alienation festering in our modern society. There seemed to be no solutions, only bitterness, anger and unremitting suffering.

After three years, I had learnt the basics of my craft, but something had drained out of me. I was no longer in love with the Theatre. My enthusiasm to become an actor had died. I was marooned in unfamiliar territory. Nothing engaged my whole being. And then I met an artist.

SIGNALS GALLERY: 1964–1967

MY NEW FRIEND introduced me to the world of Modern Art, and this strange world became my next total obsession. I began by holding exhibitions in the family home. In the early sixties support for modern art and the avant-garde was still in its infancy. Sir Roland Penrose, whose house was filled with works of the modern masters, was a founder of the Institute of Contemporary Art and one of it’s few patrons. In order to keep the institute going, every so often he would sell a work of art and replace it with a copy; when I met him his house was already half full of copies. The avant-garde was only just surviving. The Institute was located in a terraced house in Dover Street and one of the floors provided a modest space for its temporary exhibition gallery.

I convinced my father to let me have one of his shops in the West End of London, on the corner of Wigmore Street and Welbeck Street. And there I opened my gallery which was called Signals, after a series of works by the Greek artist Takis, and with its four floors of exhibition space it became one of the largest galleries of its kind in London. In the early sixties Pop Art was the rage and the Americans dominated the scene. My gallery specialized in Kinetic Art. This is the art of movement where the artist creates change within the object, or between the object and the viewer. The Gallery represented a number of artists, most of whom lived in Paris, Rio de Janeiro and Caracas. There was a strong Latin-American representation. The Gallery with its artists surrounded by all those involved in their promotion, presentation and support, became my new community. The engagement with the artists was exhilarating; visiting their studios, planning their exhibitions, acquiring their works and sometimes even selling a piece. We held individual and group exhibitions. And when, after all the planning and preparation, an exhibition finally opened and the public who appreciated our kind of art was admitted,

there was a tremendous sense of achievement and satisfaction.

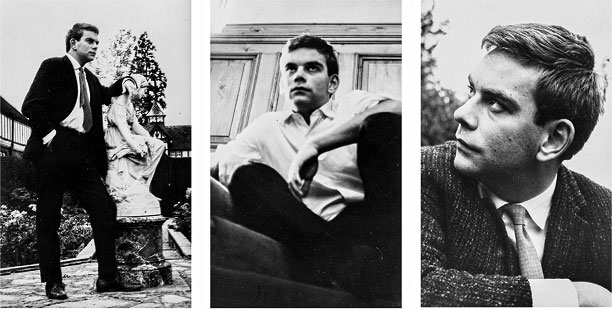

The Gallery produced a Newspaper, which, besides promoting and recording the exhibitions, brought together in its pages diverse articles, poems and pictures that explored the relationship between art, science and technology, because it was their symbiosis that was at the heart of the Gallery’s philosophy. And this picture of me standing beside one of my father’s machines, which appeared in our newspaper, sums it up.

However, the gallery was not financially viable. The sales we made hardly made a dent in the massive costs of shipping and mounting the exhibitions, producing the newspaper, and the sums spent on buying works from the artists and building a collection. Debts were mounting and the gallery was beginning to endanger the family business, so my father pulled the plug. I had to sell the collection, and the gallery went into bankruptcy. I was devastated. I was 25 and I thought my life was over. The gallery had only

been open two-and-a-half years but it had been incredibly intense and my whole being had been engaged. In the heat of the crisis I had broken with my father, and as I waited for my train on Windsor station after leaving the family home to return to London, I seriously contemplated suicide, for the only time in my life.

The gallery closed in 1967 at the time when across the Atlantic, an extraordinary rebellion of the youth of America was taking place which, when it arrived in England, was to sweep me up and take me on a strange and dangerous journey, which encompassed my life for the next year and a half.

THE EXPLODING GALAXY: 1967–1968

OPPOSITION TO THE Vietnam war had fermented a movement which had united the youth of America. The massive protests that took place had played an important part in bringing the war to an end. A section of this rebellion was inhabited by what came to be known as Hippies. Their disillusion with the established order was total. Their mantra was to turn on, meaning come

alive, tune in to the life force and drop out of the corrupt, moribund existing order. They wished to create an alternative world of peace and love.

It was through music that the Hippy tribes gathered to celebrate their new found liberation. Sound made possible by loud speakers that could carry the music to a million ears in an environment of flashing, melting, strobing lights, and with the addition of mind enhancing substances brought this strange congregation to a state of collective ecstasy. Having rejected their Christian heritage, they sought spiritual solace in India, and the gurus and maharishis flocked to America and set up their ashrams, now and then appearing at the great gatherings of the faithful, where the peace they promised mingled with the frenzied music of the bands. In England the Beatles were transformed into a band whose music perfectly encapsulated the psychedelic, and their song ‘All you need is love’ became the anthem of the movement.

My home in London, which was all that I had left after the collapse of the Gallery, became the residence for a hippie commune we called the Exploding Galaxy. The house was a hive of activity where the members of the group planned and rehearsed the latest Galactic offerings. The mission of the Galaxy was to turn all of life into art. Happenings took place in parks, on buses and at the gatherings of the faithful. The Galaxy included poets, musicians, artists, writers and dancers and our productions, though they meant a great deal to us, were incomprehensible to the uninitiated. People would stand around in states of bemusement, amusement and sometimes hostility to our uninvited offerings.

The arrival of the Kathakali dance troupe from India at the Sadlers Wells Theatre made a huge impression on us. Their artistry and power of storytelling through the movement of their bodies, hands, faces and eyes was remarkable. Accompanied by hypnotic rhythmic music, it was a mesmerising experience, and was the catalyst for the high point of the Galaxy’s short existence. The Bird Ballet, loosely based on the Persian poet Attar’s Conference of the Birds, brought together all the members of the Galaxy. Rehearsals took place in a church hall and it was staged at the Roundhouse, a large converted Victorian railway building. The Galaxy put its heart and soul into the production which lasted over three hours, however, the response from the Guardian critic was that, although he could see that the cast were enjoying themselves, he had never been so bored in his life.

But time was running out. Our happy community, living at 99 Balls Pond Road, was oblivious to the misery we caused to our neighbours, living in the adjoining terraced houses. Hippies were not popular. Our impromptu happenings had upset members of the public, and articles appeared in the press attacking our way of life. The police moved in and planted drugs in the Church hall where we were rehearsing, and then in the house. Meanwhile, a young incredibly rich French heiress appeared and started spraying money in all directions, some of which fell upon the Galaxy, which set in motion an exodus of members on the Hippie trail to India. I was taken up with organising our defence which turned into a campaign, involving the support of prominent people and the press. After months of court appearances most of the charges were thrown out. In the end the eldest member of our community was made the sacrificial victim and fined.

The spell had been broken, the community was scattering and it was at this low point I met two people who would completely transform my life. The first was the lady who would become my wife, and together we were invited to a private concert of North Indian classical music.

3

THE ABODE OF PEACE

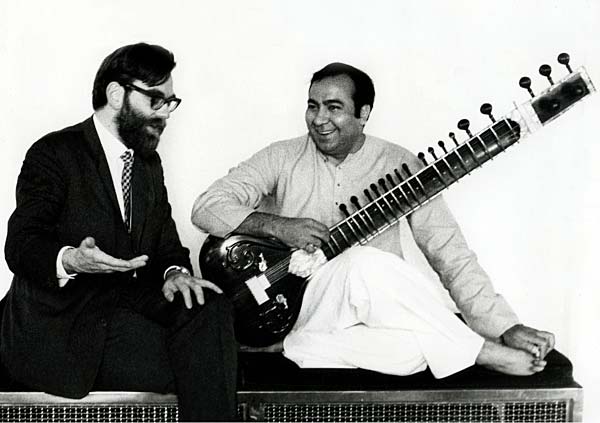

USTAD MAHMUD MIRZA: 1968

THE MEETING WITH Ustad Mahmud Mirza introduced us to a completely new world of art. His music was steeped in tradition, and because it was improvised it was fresh every time he sat down to play; it provided a structure which allowed the artist to be filled with inspiration and delve deep into the nature of the music. With his mastery of the instrument and his profound understanding of the system, he unfolded the Raga taking us to a place of peace and beauty, the like of which we had never experienced before. Here, at last, was an art form that encompassed art and science, and was wholly alive. We became inseparable from him.

Within a short time, he had me back into a world of normality. It was as though he had plucked me out of a stormy sea where I had been drowning, shaken me off, and placed me on dry land. We had all wanted to go to India, but India had come to us, and it was a very different India from the one we had been expecting. Over the winter of 1968-69 I showed him the sites of London and he began to introduce me to the world from which he came. He guided me into marriage which led to reconciliation with my family.

And then, in the Spring of 1969, full of his music, I departed for America where I organised a series of concerts on the East coast, from Washington to Boston. At Brandeis University I organized a two-day Festival entitled ‘The Mughal way of Life’. I wanted to place the music in its Mughal court setting, so that people could understand the environment where the music had developed and flourished. On the Friday, the audience were introduced to miniature painting and poetry, and there was a performance of Kathak dance. On the Saturday, Mahmud gave a concert. It was a great success and I repeated the event when I returned to London in early 1970.

THE WORLD OF ISLAM FESTIVAL 1970 – 1976

IT WAS IN Spring of 1970 that I had the great inspiration of my life, which was to provide me with my path to Islam. One of the aspects that interested the artists of my Gallery was geometric pattern, and being mostly from Latin America they were inspired by the Alhambra. I therefore knew something about Moorish Spain. Mahmud was introducing me to Mughal India, and I could see that these two cultures belonged to the same world, but the only thing that connected them was Islam. Inspired by this realization I hurried to the Institute of Contemporary Arts, where I had friends from my Gallery days, and proposed a celebration of the arts of The World of Islam.

By now modern art and the avant-garde had risen in the world and the ICA was housed in a magnificent eighteenth century building overlooking St James’s Park. The Mughal Festival had taken place at the Institute, and had been a success, so the Director agreed to host a World of Islam Festival in the winter of 1971. The Festival duly took place; the centre piece was an exhibition devoted to Islamic Pattern. This was accompanied by lectures, poetry readings and the first appearance in London of the Mevlevi from Konya, who performed their whirling dance to the accompaniment of the finest classical musicians from Turkey. Ustad Mahmud Mirza gave two concerts. The Festival was opened by HRH Princess Margaret and lasted 21 days. It was well received by both public and press.

But there was a problem. Six months before the opening of the Festival, the ICA found itself short of money, and the Director informed me the they would be unable to fund the event, so that I had to either raise the money myself or cancel the Festival. I raised some, but when the Festival closed I was £10,000 short. This was a huge sum of money in those days. I was facing another crisis.

The Festival closed in December 1971, and my eldest brother was getting married to a Swiss lady in January 1972. I flew out to Switzerland a week before the wedding, and stayed in a chalet in the mountains, to contemplate my situation. I asked myself the question “was the World of Islam Festival a good idea?” and the answer that came back was “yes, but it has to be done at the highest level, involving all the major institutions and engaging all the vehicles of presentation, and it must be opened by Her Majesty the Queen”. The outstanding debt of the 1971 Festival would then become part of the preparatory costs for the main event.

On arriving back in London, I went to the Arts Council of Great Britain. The Project needed an anchor institution and the Arts Council would be perfect for this role. It could organise and hold, at it’s Hayward Gallery, the centre piece exhibition, which was to be ‘The Arts of Islam’. My proposal was well received, but there was a problem: the present Chairman of the Exhibitions Committee didn’t like Islamic Art and so the proposal was unlikely to get through. However, he retired in a year and they had no doubt that with the new Chairman it would be passed. I had to keep my ship afloat for a year. So, what I did was to approach the other institutions and keep my creditors fully abreast of what I was doing.

I proposed exhibitions of Islamic Science to the Science Museum, Holy Qurans to the British Library and the theme of ‘Nomad and City’ to the Museum of Mankind. I proposed that the British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum highlight their vast collections of Islamic Art, and put on special exhibitions. The Horniman Museum had a fine collection of musical instruments and I suggested this could form the kernel of a loan exhibition. The suggestion to the Commonwealth Institute was for an exhibition of the Arts of the Hausa of Northern Nigeria. I discussed with The School of Oriental and African Studies and universities with centres of Islamic studies ideas for holding lectures and seminars. I approached the Southbank Concert Halls for a series of recitals of Music from the World of Islam.

The BBC was basking in the international success of it’s documentary series Civilisation. To them I proposed a series on the World of Islam, which was considered and then turned down. The reason given was that there was simply not enough interest, nobody knew or cared about Islam, it was a non-starter for television. I have lived to see Islam in the West going from being a non-issue to becoming the big issue!

Two years later, after the oil crisis had brought the Arabs to centre stage, the BBC returned, now interested in a series. But by then the Trust I had formed to organize the Festival, was making it’s own series, which the BBC then bought, showing it three times during the Festival. The response from all the institutions, save the BBC, had been very positive, but had been dependent on the Arts Council’s agreement to stage the centre piece exhibition. So it was a great relief when, at the beginning of 1973, my long wait came to an end, and I received the news that the Exhibition Committee had agreed to hold the exhibition and had set aside £200,000 for the project. All the other institutions agreed and we embarked upon the most comprehensive presentation of a civilization ever to have been mounted in the West.

The Festival took place over several months in 1976, and was opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth. Over 6000 objects and manuscripts, from 250 public and private collections, from 32 countries were gathered together and displayed in a dozen exhibitions across the capital. The universities and learned societies organised 162 lectures and 53 days of seminars. 20 music recitals were held and over 50 publications generated. A huge investment was made by the British institutions, and nearly £3 million raised from the Islamic world.

In 2010 I presented to the Centre of Islamic Studies at the University of Cambridge, the five volumes of press cuttings that covered every aspect of the Festival. This is now a record of note as it shows the response in England to Islam in 1976. The festival had a profound effect on many people’s lives, and there followed a tide of interest across the Islamic world, with the establishment of a number of Museums and cultural centres.

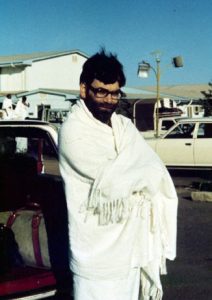

But for me it was my journey to Islam. From my meeting with Ustad Mahmud Mirza in 1968 to the opening of the Festival in 1976 I was increasingly surrounded by the beauty, truth and goodness of Islam. I had access to the finest manuscripts and works of art, the leading scholars of art, and musicians from many parts of the World of Islam. I was surrounded by Muslims who had become my friends, and six months before the Festival opened, I entered Islam. After the Festival closed, at the end of 1976, I made my pilgrimage to Mecca and became part of the Ummah.

But for me it was my journey to Islam. From my meeting with Ustad Mahmud Mirza in 1968 to the opening of the Festival in 1976 I was increasingly surrounded by the beauty, truth and goodness of Islam. I had access to the finest manuscripts and works of art, the leading scholars of art, and musicians from many parts of the World of Islam. I was surrounded by Muslims who had become my friends, and six months before the Festival opened, I entered Islam. After the Festival closed, at the end of 1976, I made my pilgrimage to Mecca and became part of the Ummah.

MASTERS OF TRADITION

I HAD NOT been seeking a religion. It was through the Masters’ of the Traditional Arts that my soul had been opened to the beauty, truth and goodness of Islam.

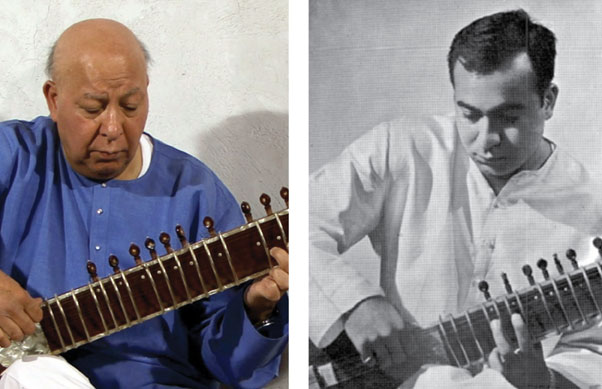

Ustad Mahmud Mirza

And the first of these traditional masters was, of course, Ustad Mahmud Mirza, who through his music, revealed to me the oceanic depths of a living tradition, compared to which the modern forms of art that I had been immersed in were like stagnant pools. For over 50 years I have witnessed the glorious unfolding of Mahmud’s music, as he remained true to his tradition, when all around him, it was being transformed into a frenzied, celebrity-driven form of entertainment.

Abdel Wahid El Wakil

And then there was the great architect Abdel Wahid El Wakil. In the 1960’s he went to Ain Shams University in Cairo to study Architecture. They taught classical and modern architecture, however, Islamic architecture, which he wanted to study – it being the architecture of his Egyptian heritage, was not in the curriculum. A friend introduced him to Hassan Fathi. Hassan Fathi had single-handedly revived the traditional architecture of Egypt. He discovered it in villages in Nubia, about to be destroyed by the building of the great dam. He rescued it by employing stonemasons who could build perfect domes and vaults, without scaffolding, in mud brick. His book Architecture for the Poor became hugely influential. Abdel Wahid became his student.

I had the privilege of meeting Abdel Wahid el Wakil in 1982. I already had a love of Islamic architecture, but he really opened my eyes and over the many years of our friendship, has taken me ever deeper into an appreciation of this supreme tradition. Working within the tolerance of the natural building materials, such as wood, brick, and stone, forms can be naturally created which resonate with the human soul. This is a fundamental principle of traditional architecture and informs all of El Wakil’s work. In the early 1980s he embarked upon a truly astonishing series of mosques in Saudi Arabia. Between the Holy cities of Mecca and Medina, a dozen buildings rose up in which he drew references from across the Islamic world and integrated them into a perfect harmony. The first of these was a small mosque, built on an island off the Corniche in Jeddah. Then there was the rebuilding of Quba, the first mosque of Islam. And the rebuilding of Qiblatayn, the mosque of the two Qiblas. There followed others, each extraordinary in it’s own way, including Miqat, the mosque where the pilgrims prepare for their entry into Medina, a majestic complex of surpassing beauty with the most memorable of minarets. The sophistication of its design is truly remarkable. During this inspirational unfolding of creativity, he gathered together master craftsmen from many places, and even revived crafts where necessary. The work of stonemasons, brick layers, metal workers, tile makers, carpenters, carpet weavers and calligraphers was brought together into a harmonious celebration of beauty.

How this miracle was achieved, in the face of the rampant modernisation that was taking place, is still a mystery to me. But part of the answer has to be the profound and steadfast commitment to the tradition of Islamic Architecture, that is Abdel Wahid el Wakil.

Anthony Milroy

My gateway into an understanding of traditional husbandry and farming in Dar al Islam was provided by Anthony Milroy whom I met some thirty years ago.

As a young man, fresh from agricultural college, he was sent to the Yemen, which was in the process of opening up to the World. His mission, from the Overseas Development Agency that had contracted him, was to see what help the Yemen needed in the development of their agriculture. After several months living with the farmers of North Yemen, the land of the mountain terraces, he realized that he had nothing to teach them. They were the masters of their environment and he became their student, and began studying their traditions.

The terraces were hard land, where the walls had to be continually maintained to contain the precious fertile soil that had nurtured by generations of farmers. They were at the head of a system that lead down into the naturally rich and fertile wadis. When the monsoon arrived it would cascade upon the mountain tops, watering the trees, and then the water would course through the terraces, and by the time it arrived in the valley below it would be a controlled flow, ready to enter the fields of the lowland farmers. Ridges separated the fields and when the water had been held for a sufficient period, the ridges were breached and the water flowed into the next field. For the children it was a time of high excitement as they played in these seasonal lakes and were carried by the flows. By the time the water had reached the end of the wadi, the community had secured its crop. The whole operation needed the engagement and collaboration of the entire community for a successful outcome, and no one was more important than the water master, who insured that everyone had their fair share. Tony Milroy was in awe of the sophistication and wealth of this traditional system of husbandry, which was transmitted through poetry, as son followed father in the field. A living tradition, increasing its knowledge as the practical experience of each generation was passed to the next generation, as had been since time immemorial.

After four years, Tony Milroy was ready to submit his report. He stated that Northern Yemen was an arid land, which had been successfully farmed for thousands of years. Every inch of land that could be, had been brought into cultivation. The farmers harvested every drop of water from the monsoon for their crops. They had developed every kind of crop that grew naturally in their environment, and were continually improving their seed stock. Their system of husbandry was completely integrated into their religion and way of life, and was a perfect example of how to live sustainably in the fragile arid zone. The only way we can help them, he stated, was to keep out. The response to his report was not favourable to put it mildly. The idea that there was any future other than the development of modern industrial farming was untenable, and it was considered that Milroy had wasted four years of the Agency’s money, studying a system that belonged to the past.

Milroy went and spent ten years studying the arid lands of the United States and Australia, and then returned to North Yemen where he found that everything he predicted would happen if the West intervened, had taken place. Europe and the US had flooded the market with their subsidised wheat, undercutting the sales of the staple crop, sorghum. This triggered a migration of the farmers from the terraces, to the oil fields of the Gulf, and as far

away as the orange groves of Florida and the almond plantations of California. Without maintenance, the terrace walls crumbled and the monsoon carried the debris down the mountainside into the wadis below. Without the terraces to channel and control the flow of water, flooding ensued, and the rich soil that had been brought from the terraces was lost to the land below. The Western consultants advised using the water table, and now Yemen faces an immanent water crisis, it’s simply running dry. Khat, a mild stimulant which traditionally was used sparingly, has now turned into an epidemic. Grown on an industrial scale, it is responsible for seventy percent of water consumed, and the chemicals used in its production are causing cancers and other health

problems. A once happy and self-sufficient people have been plunged into a quagmire of dependency, in the space of a few decades.

Sheikh Abdel Razzaq

Whilst most of the traditional arts of Dar al Islam have either disappeared or are endangered, there is one that is wholly intact: Tajweed; the art of recitation of the Holy Quran. There are many masters who still retain the knowledge of this, the first and the supreme traditional art of Islam. Some years ago, when my son Ali was in his early twenties, he decided to go to

Damascus to study tajweed with a master. Ali was a born musician, and had learnt the violin from the age of six. I asked him how he thought he would get on. He replied that he was a classically trained musician and this was only recitation, it shouldn’t pose a problem.

Ten years later, when he received his Ijaza from Sheikh Abdel Razzaq, I reminded him of the conversation we had had on the eve of his departure to Damascus, and I asked him “how does it seem now”. “Dad I’ll tell you” he replied, “There’s a great ladder and my Sheikh is right at the top, and I have put my foot on the first rung”. When I related to Ustad Mahmud Mirza what Ali had said, he smiled, “now he understands”. Ali had entered the fathomless ocean of the Holy Quran.

It is now over fifty years since I began my journey into Islam, and the journey continues…..